Mediating Bullying Complaints: Taking an Occupational Health and Safety Approach

Moira Jenkins, argues that mediation is appropriate to deal with many mild workplace bullying allegations as long as the power dynamics are addressed and a risk management approach is used.

Mediation is a common intervention in all sorts of disputes, including family court disputes, small business disputes and industrial disputes. When discrimination or sexual harassment complaints (which arguably can be a form of bullying) are lodged through external regulatory authorities such as State anti-discrimination bodies or the Human Rights Commission, the first thing these agencies do after assessing the complaint is attempt to resolve the issues through a conciliation process (which is effectively mediation within a legal framework). Under the previous South Australian occupational health and safety legislation, bullying complaints that are unable to be solved by SafeWork SA were mediated in the Industrial Commission. However, despite this, the appropriateness of mediating complaints of workplace bullying in the workplace is a hotly debated anc contentious topic. Despite this, research shows that the main approaches taken by organisations to address workplace bullying complaints are usually conciliatory (Saam, 2010, Salin, 2008, 2009), rather than punitive.

This paper argues that trained and professional mediators can effectively mediate bullying complaints if the power dynamics between the parties are successfully addressed the alleged bullying is mild in nature. Furthermore if a and a risk management approach to the dispute is taken during the mediation, risks associated with the development of bullying and the escalation of the conflict can be identified and perhaps addressed. In taking this approach the mediator needs both parties to help identify issues that may have contributed to the development and maintenance of the bullying allegation. Untrained individuals including managers, HR consultants, psychologists and others who have not received appropriate professional mediation training should not attempt to mediate these disputes.

For the purposes of this article, workplace bullying means:

“any repeated behaviours that target (either intentionally or unintentionally) an employee or group of employees, that a reasonable person, taking into account all of the circumstances, would expect to undermine, victimise, or threaten, the employees, and which potentially poses a risk to the target/s health and safety.”

This description takes into account the repeated nature of the negative behaviours, the power difference, and the potential threat to the target’s health caused by the unreasonable behaviours. It is because of this potential to cause harm that bullying is viewed as an Occupational Health, Safety and Welfare (OHSW) concern (Dollard and Knott 2004; Caponecchia and Wyatt 2007) and is part of occupational health and safety legislation in many Australian jurisdictions.

In order for mediated outcomes to be sustainable, this OHSW approach to bullying needs to be taken. This means that mediators need to address not only the relationship between the parties, but work with the parties to the dispute to identify organisational risk factors that may have contributed to the development and escalation of the behaviours.

While it is arguable that identifying risk factors in the workplace environment is conventionally not the job of the mediator, the research that identities risk factors that contribute to bullying, suggests that if a mediation settlement is to be sustained these risk factors, need to be addressed. Pre mediation conferences provide the opportunity to discuss these variables with the parties through climate surveys and discussions addressing possible antecedents or background factors that they believed contributed to the dispute. Specific consent can be obtained to provide this information to HR. During these pre-mediation meetings, the mediator is consistently assessing the appropriateness of mediation as a dispute resolution option, and the preparedness of both parties for mediation. At any time, they are able to halt process and recommend alternative processes.

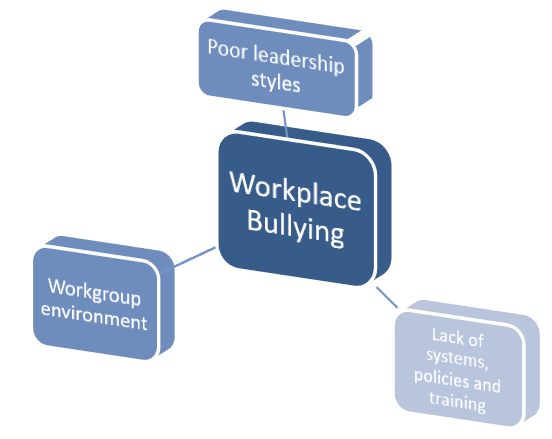

As illustrated in Figure 1 a number of factors have been found to contribute to workplace bullying. Without taking these into account, mediation on its own may be futile in sustaining long term resolution.

Figure 1: Factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of workplace bullying

Although most mediators would like there to be a balanced power relationship between disputants, this type of relationship is not the norm in any mediation (Moore 2003). Therefore, because a power imbalance is one of the features of workplace bullying, one of the primary roles of the mediator is to manage the power relationship between the parties (Wall 1981). Some of the ways in which this can be done is through the use of support persons, making sure that both parties are aware of their rights and are familiar with the mediation process. Other strategies such as reality testing the options available to both parties should the mediation not work or holding individual sessions if need be, can also assist in balancing the power differences between parties. The importance of conflict coaching as a pre mediation intervention cannot be underestimated as it helps prepare the parties for the mediation and assists them to view the dispute, and options for resolution from a number of different perspectives.

When mediating allegations of workplace bullying mediators should also be aware of the impact of being accused of bullying ( Jenkins, Winefield& Sarris, 2011; Jenkins, Zapf, Winefield & Sarris,2011), and remember that many employees use the term ‘bullying’ loosely, describing workplace conflicts and a number of other types of disputes as bullying (Liefooghe, Mackenzie-Davey, 2003; Liefooghe& Olafsoon, 1999).

Discussing the ‘Best Alternative to a Mediation Outcome (BAMO)’ and the ‘Worst Alternative to a Mediation Outcome (WAMO)’ with the parties may assist them to be more realistic about their expectations in mediation, and understand the ramifications for them if the mediation does not resolve the underlying differences. Complainants that choose mediation as an option within an integrated conflict management system, usually have a choice to have the complaint investigated if the mediation is unsuccessful or the conflict continues following mediation. Mediators who believe that one party is disadvantaged by the mediation process, and cannot participate fully are able to stop the mediation, and suggest that alternative processes to addressing the complaint are instigated.

In most states in Australia bully targets also have the option to make a formal complaint outside the organisation to an external government OHSW jurisdiction at any time. If the bullying involves sexual harassment, or other behaviours that target an employee’s specific characteristics such as race, age, sex or disability they may also be able to lodge sexual harassment or discrimination complaints with their State anti-discrimination commission or the Federal Human Rights Commission. There are advantages and disadvantages of both of these options that can be discussed with both parties.

Confidentiality in mediation is never absolute, and mediators have a duty of care to stop mediation and follow up any threats (either explicit or covert) to the safety of either party.

When there have been allegations of workplace bullying, it is recommended that a copy of the settlement agreement be provided to a third person who will follow up with both parties that the agreement is being adhered to. It is often in the interest of both parties that this is carried out, and in my experience it is something welcomed by both the complainant and the party accused of workplace bullying. It is also recommended that human resources (HR) or senior management is informed about any systemic or organisational issues that are identified during the mediation that may have contributed to the conflict. Permission can be granted by the parties to do this, and again this is a recommendation that is often welcomed by mediation participants.

Some of these wider issues might include unclear job descriptions and roles, job insecurity during significant change, lack of processes or identified guidelines in regard to organisational proceedings, poor team morale and high conflict, lack of training in new technologies contributing to conflict and insecurity, high workloads and staffing issues. There may be times where it is appropriate for a third party to be brought into the mediation to clarify roles, jobs and responsibilities. This can be carried out during private sessions or during the mediation itself if appropriate.

While individuals are encouraged to take responsibility for their past and future behaviour, it is important that a workplace culture that is permissive of inappropriate behaviours is brought to the attention of HR or senior management. Permission can be granted so that these broader issues can be raised without breaching the confidentiality of the dialogue between the parties during the mediation.

Raising these systemic issues can be framed as benefiting both parties to ensure that they both receive support to comply with any settlement reached, and the workplace environment also supports appropriate behaviours. Conflict coaching is another tool that can be used either before mediation, or following the mediation to assist the parties to identify how their behaviours may have contributed to the conflict, how the other party might view the conflict, and to provide a structure so that they have additional skills for more effectively addressing the issues.

This approach to mediating bullying complaints focuses not only on mediation itself, but also the organisational dynamics that have been shown to contribute to the development and maintenance of workplace bullying.

It is recommended that ADR practitioners who are mediating workplace bullying complaints become familiar with the workplace bullying literature and the identified risk factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of workplace bullying. This is because these background factors if not addressed, may contribute to the breakdown of mediated settlement agreements and further bullying and pose an ongoing risk to the health and safety of vulnerable employees.

The author:

An experienced psychologist, Moira has worked as a mediator, trainer and conflict coach and was the Manager of the Complaint Handling Section of the South Australian Equal Opportunity Commission where she investigated and conciliated complaints of sexual harassment and discrimination. Moira holds the title of Adjunct Lecturer in the School of Psychology at the University of Adelaide, where she provides input into the Masters of Organisational Psychology program.

Moira has postgraduate qualifications in mediation and conflict management, has undertaken LEADR mediation training, as well as conciliation training through the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Her Doctoral thesis was titled: Workplace Bullying: The Perceptions of the Target, the Alleged Perpetrator and the HR Professional: Integrating Stakeholders Voices to Improve Practice and Outcomes.

Moira has assisted organisations with the development of policies and complaint systems, in the management of workplace bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination. She has facilitated full day workshops on mediating workplace bullying complaints from an OHSW framework for LEADR, and a number of other private industry partners. Full day workshops on preventing and managing workplace bullying from an OHSW perspective have also been conducted for a number of other organisations. Her book Preventing and Managing Workplace Bullying and Harassment: An Occupational Health and Safety Perspective is currently in publication with Australian Academic Press.

References

Caponecchia, C, and A Wyatt. 2007. The Problem with “Workplace Psychopaths”. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Occupational Health and Safety 23 (5):403-406.

Caponecchia, C, and A. Wyatt,2011. Preventing Workplace Bullying: An evidence based guide for managers and employees. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW.

Dollard, M., and V. Knott. 2004. Incorporating psychosocial issues into our conceptual models of OHS. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety 20 (4):345-358.

Jenkins, M. F., Winefield, H. & Sarris, A. (2011). Consequences of being accused of workplace bullying: An exploratory study. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 4(1), 33–47.

Jenkins, M. F., Zapf, D., Winefield, H. & Sarris, A. (2011). Bullying allegations from the accused bully’s perspective. British Journal of Management. (Available online)

Liefooghe, A. & Mackenzie-Davey, K. (2003). Explaining bullying at work. Why should we listen to employee accounts? In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice. London Taylor & Frances.

Liefooghe, A. & Olafsoon, R. (1999). Scientists and amateurs: Mapping the bullying domain. International Journal of Manpower, 20(12), 39–49.

Moore, C. 2003. The mediation process: Practical strategies for resolving conflict. Third ed. San Fransisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass.

Saam, N J. 2010. Interventions in workplace bullying: A multilevel approach. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 19 (1):51-75.

Salin, D. (2008). The prevention of workplace bullying as a question of human resource management: Measures adopted and underlying organisational factors. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24, 221–231.

Salin, D. (2009). Organisational responses to workplace harassment. Personnel Review, 36(1), 26–44.

South Australian Occupational Health Safety and Welfare Act (2006) Section 55 A (3)

Wall, J. 1981. Mediation: An Analysis review and proposed research. Journal of Conflict Resolution 25 (1):157-180.